Learn Spanish Using Your Visual Memory

Is it possible to quickly learn and effortlessly remember new Spanish words or any other language’s words and phrases?

The short answer is both yes and no. For a few people who learn how to retain words and language (sounds) by using their visual memory (pictures), this will seem like a miracle. They will learn very quickly. But most people won’t get much out of this approach.

To understand the paradox of why learning sounds using mental pictures will work like magic for some learners but not for most learners, you need to know more about the very important thing you are trying to change when you learn Spanish or your favorite new language, which is . . .

your brain.

Let’s start with some basic brain science.

The video below features MIT graduate student Evan Ehrenberg explaining the large parts of the brain and what they do.

Watch the video from where I set it to begin, and then stop it at the 1-minute mark (1:00) when you hear Evan say, “The occipital lobe here in the back handles vision.” That’s all you need from the video.

Your occipital lobe, the part in the back, acts like a “work to the rules” employee that usually won’t give you even a tiny bit of help with language learning.

If you can trick your occipital lobe (and also your hippocampus) into helping you learn languages, you will be able to achieve the kind of effortless and fast learning that polyglots talk about.

Later in this article, I’ll give you a simple quiz to see if you’re ready to start using your visual memory to help you learn foreign languages quickly, or whether you would be wasting your time.

Key Neuroanatomy for Language Learning

Now look at a different drawing that shows the important points from that video more precisely. Click on this link to open a new tab with a drawing that shows the relative size of your auditory and visual cortices.

The most important part of your brain for hearing is a relatively small part of the temporal lobe called the audio cortex. For 90 percent of people, this will be on the left side of the brain.

The most important area for vision is your primary visual cortex. This makes up a relatively larger portion of your occipital lobe.

And there is one more important part of your brain that is not used nearly enough by language learners but is used well and often by polyglots, and that is your hippocampus.

If you lose both of your hippocampi (you have one on the left and one on the right side of your brain), you will not be able to form new long-term memories.

Your hippocampus handles spatial memory and the transition of short-term to long-term memory. It’s what helps you remember where you put your car keys and which dresser drawer has your underwear in it.

How Your Brain Learns

A practical way to think about how your brain learns is to simply remember three things about your brain.

1. Bigger is better. The more parts of your brain you can use to learn something, the easier it will be.

2. Spatial memories are better than non-spatial memories. Spatial memories (and much of all learning) is handled by your hippocampus. And activating your hippocampus the right way is key to easily forming new long-term memories.

3. Strange is better than ordinary. Your brain does not pay much attention to (or remember easily) the things that are ordinary.

Your Brain as a Group of Computers

You can think of each part of your brain as a specialized computer that normally only does one job.

When a signal comes in from your nose, it goes to your olfactory bulb. When a signal comes in from your eyes, it goes to your primary visual cortex. When a sound comes in from your ears, it goes to your primary audio cortex.

There is more to it than that, of course, but that’s a good way to have a basic understanding of what your brain does with different types of signals.

You usually have no control over what signal goes to which part of your brain.

Look at the picture again, the one I linked to above, and remember that your visual cortex is a lot larger than your audio cortex.

The more of your brain you can involve to learn something, the easier your learning will be. And your visual cortex is big!

Visual Memory for Audio Learning?

At first glance it would seem that it is impossible to use your visual memory to learn a new language. Your brain automatically routes sounds to your audio cortex and images to your visual cortex.

That’s why, when someone is talking to us, we hear the words they say; we don’t see the words they say.

But we all know that remembering strange new pictures is much easier than remembering strange new words, so the payoff from learning to use your visual memory to solve what is basically an audio problem should be huge.

Indeed it is. Ask the polyglots!

Our Amazing Visual Spatial Memory

The typical person who can’t remember a new phrase in Spanish to save his life is a genius at remembering exactly where he caught that huge fish last summer or how to make his favorite dish from scratch.

You see, humans are geniuses at remembering pictures and spatial relationships of where to get food.

Our hunter-gatherer ancestors used these talents to hunt and gather food. If they weren’t good at finding food, they didn’t survive to be our ancestors.

We use this part of our brain to remember that the snack cakes are on aisle 9 of our supermarket.

Remembering Lists Without Your Smartphone

Today you don’t need me to tell you where to catch fish to survive, but it might be useful if I told you how to remember your shopping list without your smartphone, and it will be useful when I tell you how to remember foreign-language words more easily.

So here’s my shopping list from last week. I think you’ll be able to remember this tomorrow or next week if you do the easy mental exercise I explain below.

Here’s the list.

1. A gram scale for weighing food European-style in my kitchen

2. Black sox

3. A bottle of dish soap for washing dishes

4. Sauerkraut

5. A box of tissue paper

6. A red flashlight

So to make this list really easy to remember, here’s what you do. Think of the first six places you go when you wake up and visualize them. Then mentally put these items in those locations with strange pictures.

Here’s what my locations are in the morning: bed, toilet, bathtub, kitchen, computer.

For this to work for you, you need to think of the first six things you do. Here’s how I effortlessly remembered the list of what I do.

The usual things I do when I wake up are: I wake up in bed, then I go to the toilet. Then I take a bath, then I go to the kitchen to eat breakfast, then I read my email on my computer. I used my visual memory of this habitual sequence to remember my shopping list. Here’s how I did it.

I woke up in bed and, much to my amazement, there was a huge balance beam scale, just like they have on courtroom walls, where they are trying to explain blind justice.

Then I went to the toilet, and someone was washing black sox in the toilet. It certainly wasn’t very hygienic. Then I went to get in the bathtub, and it was full of plastic bottles of dish soap.

Next I went to the kitchen to eat breakfast, and who did I meet there but Adolf Hitler, and he’s sitting there eating sauerkraut in my kitchen.

Then Hitler stood up and started stuffing tissue paper in the back of his pants to try to make them fit better.

Then I looked at my computer and there was the strangest thing. On the keyboard (not on the screen) was a living, animated flashlight. And the flashlight was singing, “I want some red roses for a blue lady” into a microphone.

So my shopping list was a scale, black sox, dish soap, sauerkraut, tissue paper, and a red flashlight. If you actually did this with your own visual locations, you will be able to remember this list effortlessly. It could have been three times as long, and it would have been just as easy as long as you stored each item on the list as a strange visual image at a known location in your mind.

These images do fade if you don’t review them, but the number of reviews that you need is tiny compared to learning a list without a memory device like this.

So right now you are probably saying, “I have a smartphone for lists—why should I care?”

The reason you should care is that a very similar technique can be used to memorize foreign language words and phrases with much less effort than by using methods that do not use visualization.

Turning Foreign Words into Strange Pictures

If I tell you a story about something ordinary, you are likely to forget it before the conversation is over, but if I tell you about something strange, it’s easy to remember.

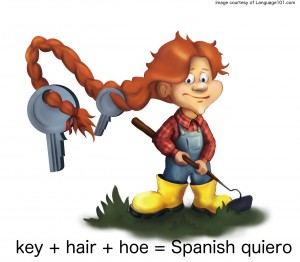

Take this story, for example. “Yesterday I met a girl with a key floating in the air behind her. The key was woven into a huge braid of her orange hair, and she was hoeing in the garden with a hoe.”

I hope you have a picture in your mind of a key and braid of hair and a hoe, something like the one below or hopefully even more strange.

Now if you happen to be studying Spanish, and if you happen to piece together the sounds of parts of key and hair and hoe while studying the Spanish word for “I want,” which is written quiero in Spanish, you may have instantly memorized the word for “I want” in Spanish.

More of your brain is used for visual memory than audio memory, so your visual memory is better than your audio memory.

So almost like magic, you have just tricked your brain into using your huge visual memory to learn a new word that you would usually have had to use your much smaller audio memory to learn.

Visualizing Sounds Is Easier than Visualizing Meanings

This is a much different approach than used by every book and every piece of software on how to learn a language. Almost every person writing an article or a chapter in a book who hopes to help you visualize and learn the word quiero would try to show a picture of someone “wanting” something.

That is the approach used by Rosetta Stone and a thousand others that don’t work. It’s always easy to remember the pictures, but remembering how to say or understand the foreign-language word will remain difficult.

Normal Pictures Are Forgettable Pictures

The other common mistake that Rosetta Stone and other language-learning program designers make is using nice ordinary pictures to illustrate words and phrases.

I hate to tell you this, but nice ordinary stock photos or even beautiful custom photos of normal things just aren’t that interesting. Yes, we do have a huge visual memory, but to engage your huge visual memory, I have to get your attention, and that’s hard to do with something ordinary.

Easy-to-remember pictures are strange, unexpected, raunchy, sexy, violent, overall unusual, and worthy of gossip. Basically the more strange the picture is, and the more action it has in it, the easier it will be to remember.

A Crazy Man in Mexico

On my last trip to Mexico, I was near Cancun in the small town of Puerto Morelos. I met a man who everyone said was crazy. In the morning, he would walk onto the beach and start yelling and wagging his finger at the sun. About noon he would come out and do it again, and just before the day was over he would come out and yell at the sun for a few more minutes.

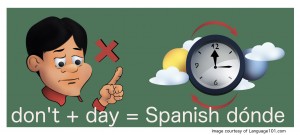

Piecing together sound-alike words from your own language to learn a new Spanish word can help you remember faster.

Now if you were studying the Spanish word that means “where,” which in Spanish is written dónde, visualizing the words “don’t + day” might help you remember the Spanish word for where.

Hearing and Speaking Are Still Necessary

It turns out that even if you get very good at this type of visualization, you still need to hear the words (sometimes very slowly), and you still need to learn to speak in your new language.

Fortunately, our software is very good at helping you hear and learn to reproduce the sounds in your new language.

For Some Language Learners, This Will Be Magic

If you can already hear and reproduce the sounds in your new language well, learning to visualize the words and phrases in your new language will be absolute magic for you.

For people who are 100-percent beginners and who can’t yet hear and say new words when prompted, you will still need to learn to hear and reproduce the sounds in your new language.

Why World Memory Champions Aren’t Polyglots

The video below shows two-time world memory champion Wang Feng being interviewed about his methods. Note that he dosn’t speak English.

Then there is eight-time world memory champion Dominic O’Brien. If you read his bio page, which lists his professional accomplishments, it doesn’t mention anything about the languages he speaks.

Here’s a video of him being interviewed on German television. The TV reporter is speaking German, but note that Dominic is speaking only English. If he spoke good German, he would probably wouldn’t be speaking English on German television.

What Are These Memory Masters Missing?

It’s my opinion that these memory masters are deaf to the sounds of other languages. While they have wonderful memorization and visualization techniques, they cannot actually perceive the sounds of the new languages they want to learn. They simply don’t have the neural circuits to differentiate and actually hear the sounds of the new languages they want to learn.

That’s why they don’t go on to become polyglots after becoming memory champions.

How to Become a Polyglot?

I believe, and I hope to prove, that polyglots have mastered two different, relatively unrelated skills. They have mastered the memory techniques taught by Dominic O’Brien and others, and they have developed advanced audio processing in their brains so they can perceive and reproduce sounds that people who aren’t polyglots cannot.

How to develop those audio and visual skills is the subject of another post.

Login

Login